The Demolished Man

Alfred Bester

1953

"In a world in which the police have telepathic powers, how do you get away with murder?

Ben Reichs heads a huge 24th century business empire, spanning the solar system. He is also an obsessed, driven man determined to murder a rival. To avoid capture, in a society where murderers can be detected even before they commit their crime, is the greatest challenge of his life."

Notes:

This book feels and sounds very much of its time, despite being a combination of speculative fiction around the concept of mind reading psychics ("espers" and "peepers") being part of society. Because the book was written before the current dependence on the internet, the limitations of espers presented by being unable to work over communications technology is not nearly as pronounced as a story on the same topic written now might be. Jungian dream symbolism as science+prophesy is also central to the book.

The characters are all depicted as flawed. No one is particularly heroic or likeable, and I spent most of the book hoping that the main character, the businessman turned murderer Mr. Reich, would meet his end.

Interestingly, though Mr. Reich sets out to use his natural killer instincts in combination with a meticulous plan and significant resources to get around the peepers and to get away with his crime, he quickly devolves into panicked animal violence and only gets away with it due to his subconscious misunderstanding on his rival's cipher response.

There was a "chosen one" plot that didn't start being developed until the final 2/3 of the book and the conclusion was both excessively convenient and vague.

Overall, I'd probably have enjoyed it more if I were into police procedurals, but I didn't hate it.

The Darfsteller

Walter M. Miller Jr.

1955

"Some men insist on competing with machines - and the essence of that contention is that, like a machine, they somehow have no ability to learn new ways..."

Notes:

I was absolutely shocked at how well a story written more than half a century ago addresses the pressing tension between AI generated media and the arts. The story follows a washed out theater star turned janitor, Ryan Thornier, whose chance at a leading role was dashed when robotic mannequins with the visage of famous actors replaced human ones in theatrical performances. Thornier refuses to sell his likeness and psychological profile for use in these "dolls," and so retains his artistic dignity at the expense of social and monetary standing, but remains affixed to a past that cannot return. His lost love, Mela Stone, was an actress who sold hers and recieved royalties, but presided over the death of human theater. Jade Ferne, a playwright, has adapted to producing plays with the mechanical actors as her way of remaining close to and relavent in the art. Each of the three have their own sorrow for the supplanting of theater with its mechanical form. Thornier considers it something to resist, hoping to return to a golden age or at least "one last great role" while Mela tries to suppress her feelings about it, even as the promised immortality of her image on the stage fades before her own natural career would have due to loss of audience interest and the dolls of her can be made to perform in base ways. Jade has come to terms with the changes, claiming "Maestro's really capable of rendering a better-than-human performance anyhow... I said 'capable of', not 'in the habit of.' Autodrama entertains audiences on the level they want to be entertained on

After a disastrous second act in which Thornier's erratic behavior causes the controlling mechanism "Maestro" to overcompensate, Mela rejoins Thornier on the stage in what was supposed to be her great role. Acting with her enables Thornier to achieve closure with the theater that he loves but which is dead and gone. "He had stood firm on a principle, and the years had melted the cold glacier of reality from under the principle."Though he planned a suicide by replacing blanks with live rounds as his grand exit, he decides to live instead, but is unable to remove the bullets before Mela is once again replaced by her doll. He is shot by the doll but survives after contemplating an ikon above a bust of Lenin in the play. "The cultural soul was a living thing and it survived as well in downfall as in victory; it could never be excised, but only eaten away or slowly transmuted by time and gentle pressures of rain wearing away the rock." His sabotage is not unnoticed and ruins the show and his last great role is a failure, but a theater friend offers to help him find a tangentially related job, not as a permanent niche but as a human whose strength lies in dynamic flexibility, not in being able to outcompete an impersonal tool.

The title "The Darfsteller" refers to an actor who "can't play a role without living it and won't live it unless you believe it." It's exactly this kind of actor who has the hardest time moving on and also this kind who producers most desired to replace because of how committed they were to their roles.

Personal Thoughts: So much of this story seems like it is written for this exact moment, though I do think it's funny that something so complex as doll actors instead of as simple as recorded performances is the projected future. It was still an analog time and like the other speculative fiction of the time, assumes people largely remain interested in physical things, which has not played out that way. The Darfsteller's (mostly) accurate assessment of computers taking over creative fields is "well that sucks but you can't fight it so move on to something else" Even if the machines are uncanny. Even if (especially because) the experience is dumbed down for mass appeal. But what does that mean for us Darfstellers for whom being a practitioner of our art is essential to our human experience?

The story would say "don't try to out specialize a tool." I don't think we'll be able to beat AI on its own grounds. But what can I do easily that it can't?

As of right now:

-Narrative structure represented visually

-Interface with the physical world

-Texture

-Curation

-Taste

-Composition inside a larger context

AI is great at static portraiture in a variety of styles, content meant to be consumed only digitally, and throwaway content. I think its telling that we dont have AI memes, even though they are low effort. They are more durable than most digital work with a lot of thought and effort behind it. I see memes from imgur that have outlasted the files of some impressive stuff from 10 yrs ago.

Good taste is too much to ask from the general public. It took half a decade for home cooks to figure out how to leverage new technologies to make actually GOOD food, not just cream of chicken soup slop meals. And to do it, it tooks a dedicated bunch of snobs in a youth subculture (hipsters). I think the internet as creative venue might survive the AI influx, but generally accessible uncurated social media will not. There is already no lack of material with no viewers and readers. And the ability to generate middling amalgamations just makes finding good stuff harder. But I can work in meatspace and I can curate my own work and engage in personal relationships with other people in a way that AI can't.

And as for new art forms that come of this? I have a nebulous idea of creating not individual pieces, but environments with which AI can interact. Factory robots work because their environments are highly controlled, as it is easier to do this than it is to create a multi-environment robot. Can an Amazon warehouse become artistic expression? Maybe! I want to explore this idea a bit more going forward.

I enjoyed this much more than The Demolished Man. The conclusion is unfortunate but mostly true and it is certainly food for thought.

"Allamagoosa"

Eric Frank Russell

1955

Honestly not a difficult short story, but abolsutely hilarious if you've ever had the misfortune of having to inspect and/or sign for anything in the military. I laughed out loud at the end. Go read it.

Double Star

Robert A. Heinlein

1956

“Exploration Team”

Murray Leinster

1956

Notes:

"menial work - a man will do for himself but wont do for another man for pay"

"robots are too much like rational animals, not men"

"Roane's convictions as a civilized man were shaken. Robots were marvelous contrivances for doing the e pected: accomplishing the planned;coping with the predicted. But they had defects...a robot civilization worked only in an environment where nothing unanticipated ever turned up, and human supervisors never demanded anything unexpected. Roane was appalled. He'd never encountered the truly unpredictable before in all his life and career."

This story starts out as adventure pulp inistinguishable from fantasy, except for that it makes use of guns and transmitters instead of swords and smoke signals. It later becomes a commentary on the need for human ingenuity and self-respect (religion) in uncivilized environments. Colonies built with robotic servants result in humans who exist to keep them working and built environments with consistency and control in mind. Man's relationship with domestic intelligent animals (bears in the story but also dogs by extension) is, by contrast, presented as a dynamic partnership.

A fun story! It wrapped up a bit abruptly but satisfactorily. I really enjoyed the illustrations.

The Big Time

Fritz Leiber

1958

An interesting idea was potential binding as the next evolutionary adaptation (memory was the previous one, allowing the binding of time as plants bind energy and animals bind space through movement).

Its a religious work, implying the maintained existence of the self beyond body and death. I dont know enough about the author to know if this is intentional.

The ending was frustrating, but a necessary one if there is no ressurection, no paradise, but only eternal unlife.

★★★★☆

A Case of Conscience

James Blish

1959

Another, less well developed theme is how the paternal treatment of children makes them hate their protectors. This is shown both in the character of the reptile child who is not given the survivalist upbrining essential to the development of his species as well as in the populations forec underground for their own protection due to the atom bomb. Not bad, but it felt more like a thought experiment than a novel.

Starship Troopers

Robert Heinlein

1960

A Canticle for Leibowitz

Walter M. Miller Jr.

1961

I liked the structure of the book. Miller shows the passage of time through the eyes of very different sorts of people in very different circumstances, but all with the unifying threads of vocation, preservation of knowledge, survival, death, suffering. The first and last act mirror each other in both funny (right to left writing) and touching ways. The dreadful hope of progress plods along through the centuries, alleviating pains, sufferings, and cruelties in exchange for new ones. The main characters of each act are responses to and refrains of each other.

The issue of state sponsored suicide is interesting as both the one that is most pressing today (vs a more distant but not negligible threat of nuclear war) as well as one that must have deeply troubled the author, who eventually took his own life in deep depression. Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman was published posthumously, and I'm interested to see if his perspective on faith and science changed in the decades between this book and that.

My favorite quote comes from the mouth of the wanderer, Benjamin, who having seen the secular second coming in the form of Thon Taddeo the scientist, reminds the abbey that, though they see an end to the age of darkness and hope to return to learning, “It’s still not him.” [Christ]

This was a great salve to a lot of my current spiritual struggles and a reminder that issues of faith are enduring regardless of the age. Redading it after The Golden Bough was interesting because it is so much later and written by a thoroughly modern man. I also liked it a lot more than The Darfsteller and it was interesting to see Miller come into his own. It's Literary as well as pleasurable and well worth the read.

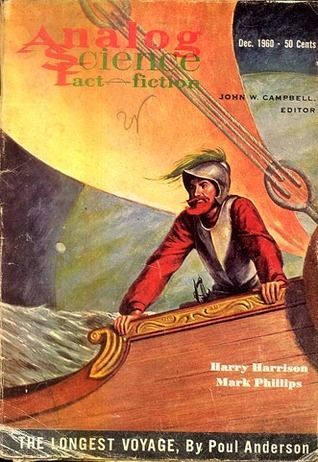

The Longest Voyage

Poul Anderson

1961

Stranger in a Strange Land

Robert A. Heinlein

1962

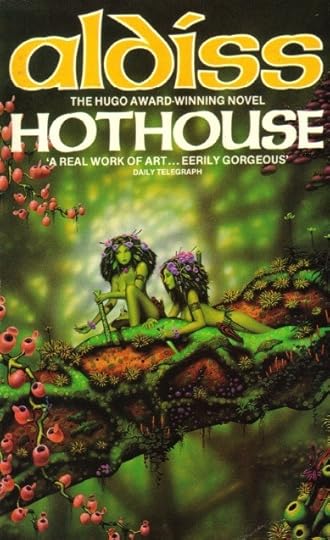

Hothouse

Brian W. Aldiss

1962

The first and third sections were a pleasure, though the middle was a bit of a slog as it was difficult to suspend disbelief both with regard to the telepathic, ancestral memory accessing parasitic mushroom as well as the attrition of adult humans making it uncertain how this could be supported by bringing up enough infants among them. A biologically focused sci-fi was a refreshing change of pace and the biblical allusions and fairy tale styling of some plot points was a little heavy handed at time but overall lent a seriousness to what could otherwise be considered a classic pulp style sci-fi/fantasy pulp novel. I also enjoyed that the two groups of humans chose two futures for themselves, continuing the divergent evolutionary theme. It's not quite Literature, definitely not Science, but is a good yarn if you are into that kind of thing.